These past days, when playing with Houdini, I was somehow really frustrated because I could not use the previous frames as input to create some faked dynamics inside my geometry block. Of course, since it’s basically for creating dynamics, I could take a look at DOPs but I don’t feel quite ready for that yet (too complicated, I’m such a slow learner).

So, I looked a little bit in the doc, the internet and tested some nodes and I found out the Node ‘Solver’ which basically does exactly what I wanted!

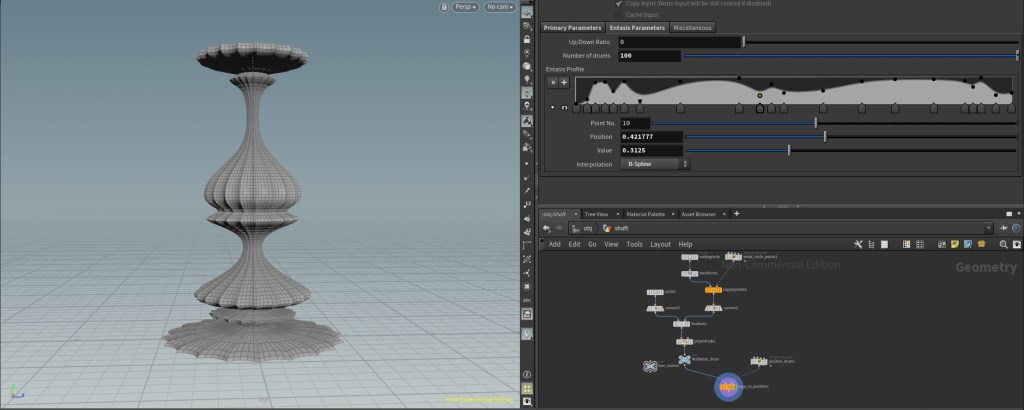

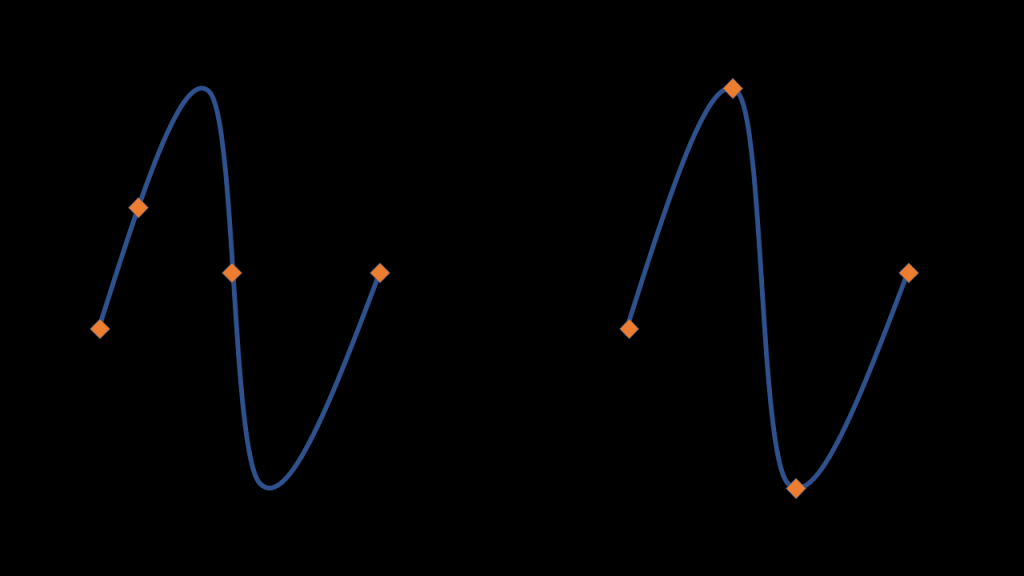

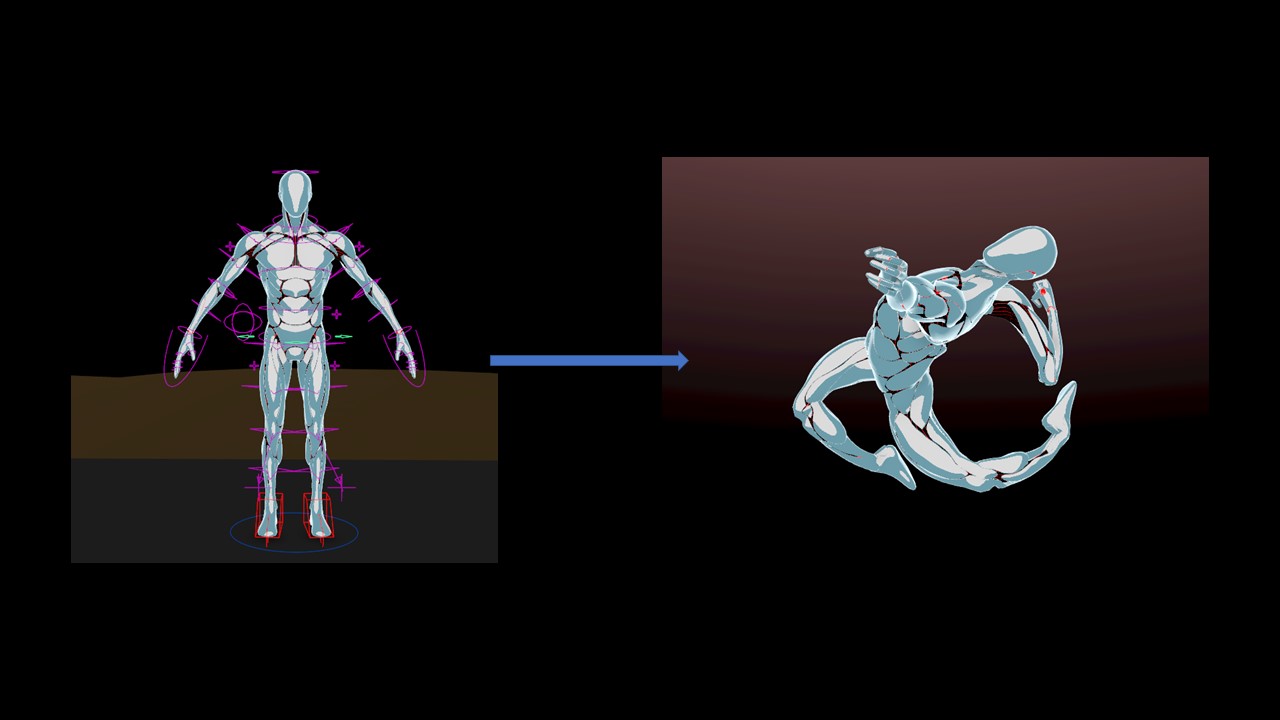

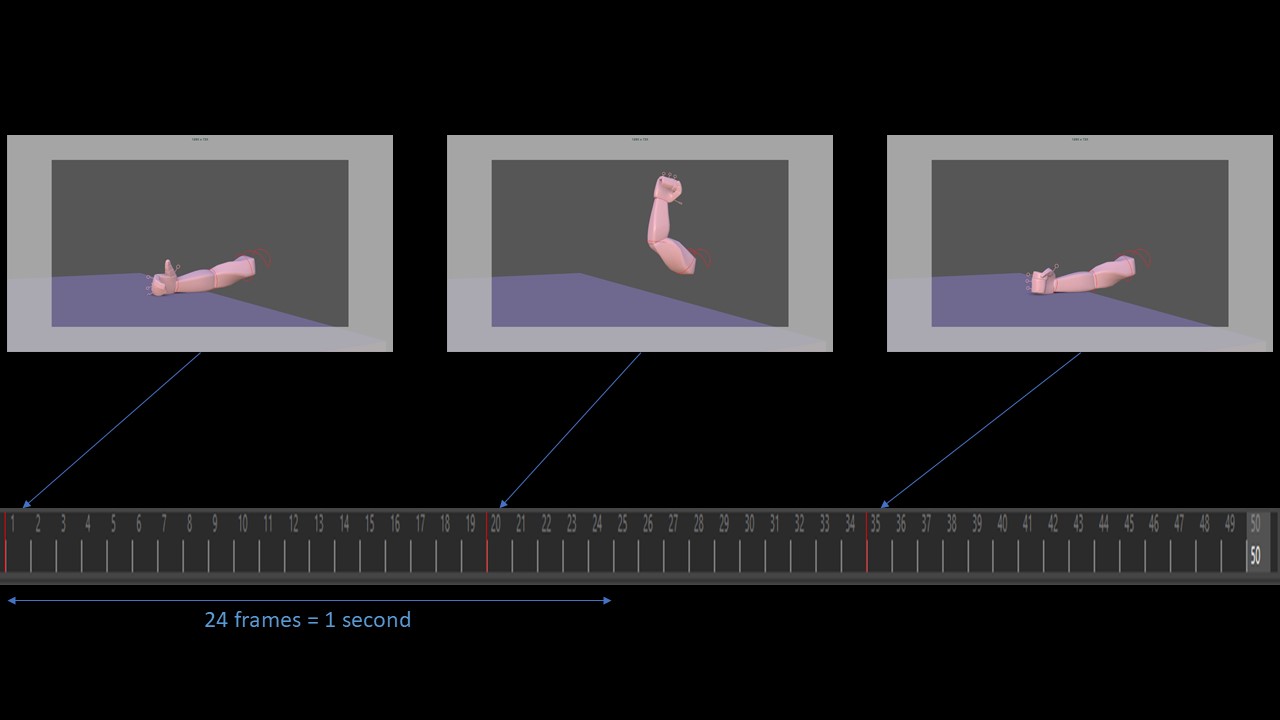

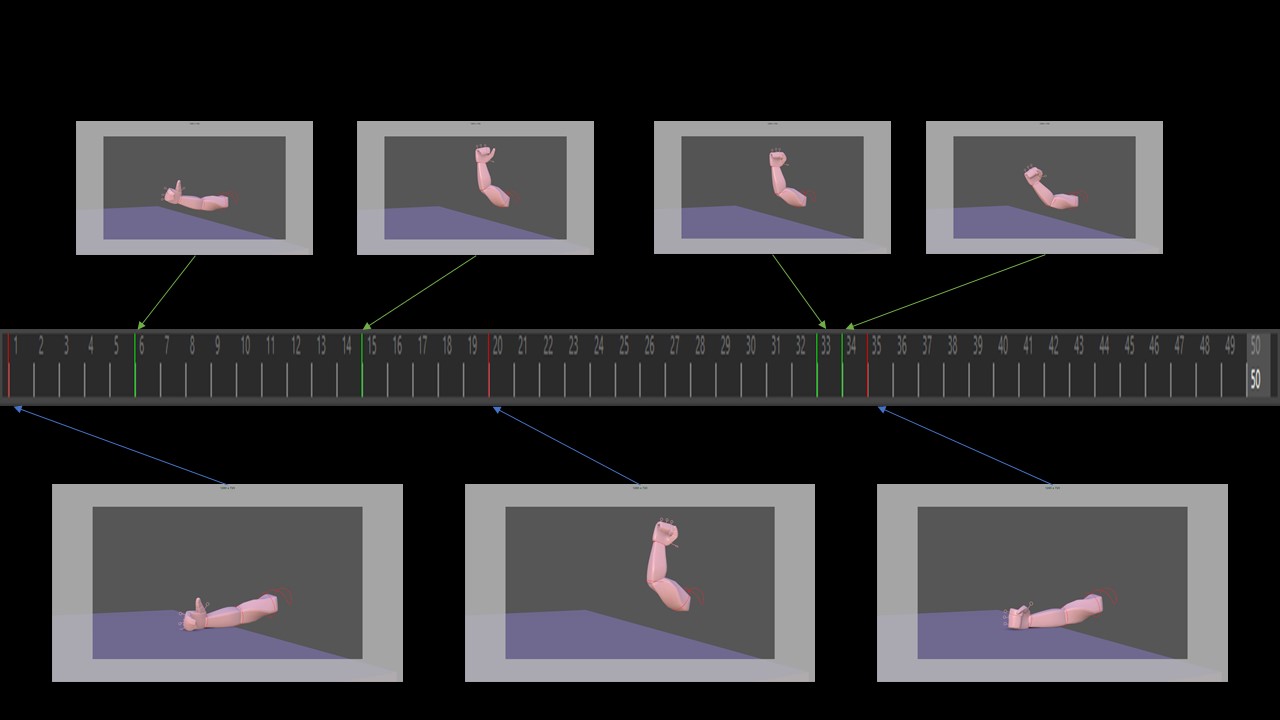

Let’s start with showing the result of today’s practice

Let me just explain quickly what it’s all about. I’m starting with a point cloud where all the clouds are neutral except a few (the colored ones). At each frame, the colorful points try to contaminate their neighbours according to a procedure that I describe below. Then, I use the time of contamination to drive a cosine displacement along the normals which creates a wavy effect.

In the upcoming paragraph I will give a breakdown of the process; in the last paragraph, I will speak a little bit about mathematics and geometry (basically, my results can somehow look like Voronoï fracture and I’m trying to give an intuition of ‘why’). I might be getting things wrong, so, as always, do not hesitate to contact me for improvement or questions!

Step 0: preparing the data

Just saying, I will apply everything to a point cloud that I will create by scattering points along a surface. Indeed, the displacement along the normals make sense only if I have normals to start with so scattering along a surface and not a density makes more sense:

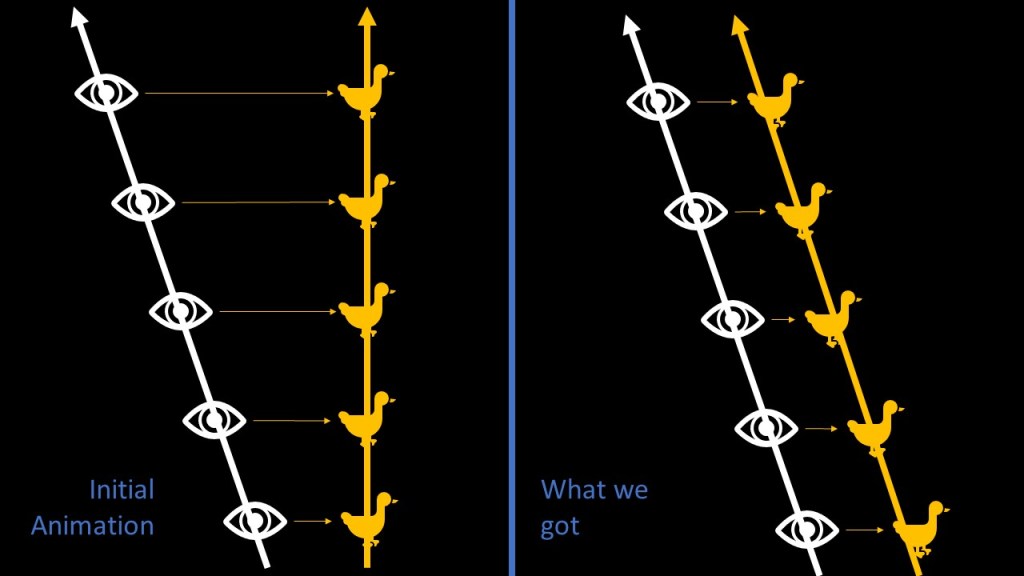

Step 1: Contamination

Basically, I’m creating clusters via a contamination process. The idea is as followed: I have some points that are contaminated. They will ocntaminate their neighbours at each frame so the contaminated part will eventually grow and all the points will be contaminated in the end. The results can change a lot depending on what the contamination procedure consists of so I’m going to explain it right now!

Of course, there are plenty of ways to define this step (and I will discuss it a little bit later) but this one is interesting because it can create some artifacts and is really easy to code -that was just a test after all 😀

Notice the green clocks: it means that, at those nodes, the geometry is animated!

Step 1.1 Initializing

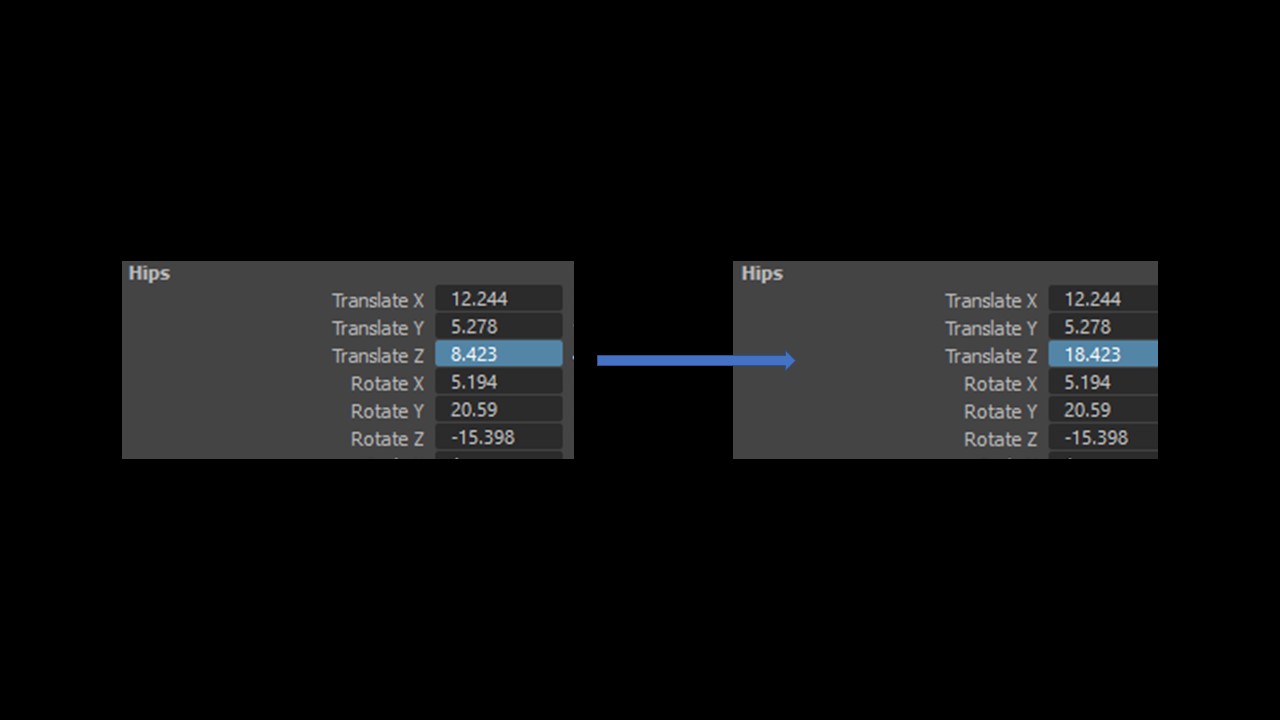

The create_attrib wrangle creates where we will store the ID of the cluster each point belongs in and a birthdate value which corresponds to the distance (in term of contamination) from the point to the origin of the contamination. The ID of a neutral point is -1. The initialize wrangle will pick a random starting point for each cluster.

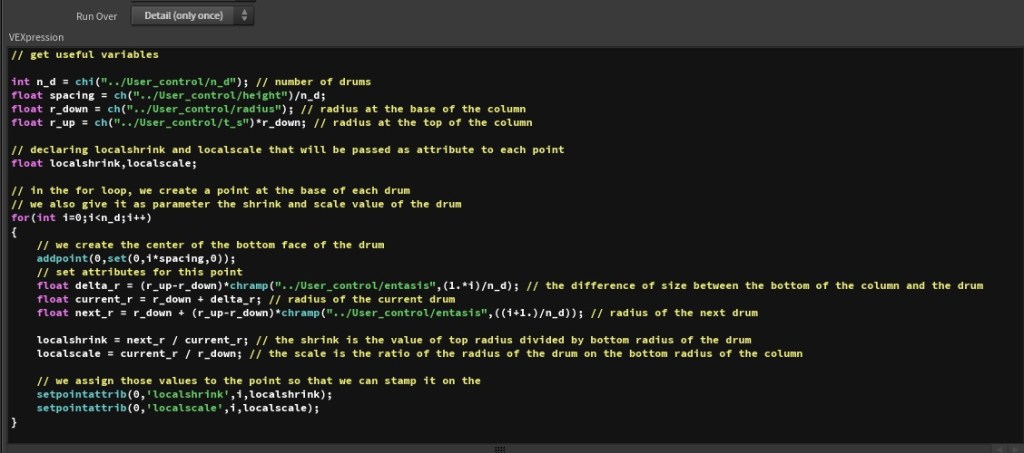

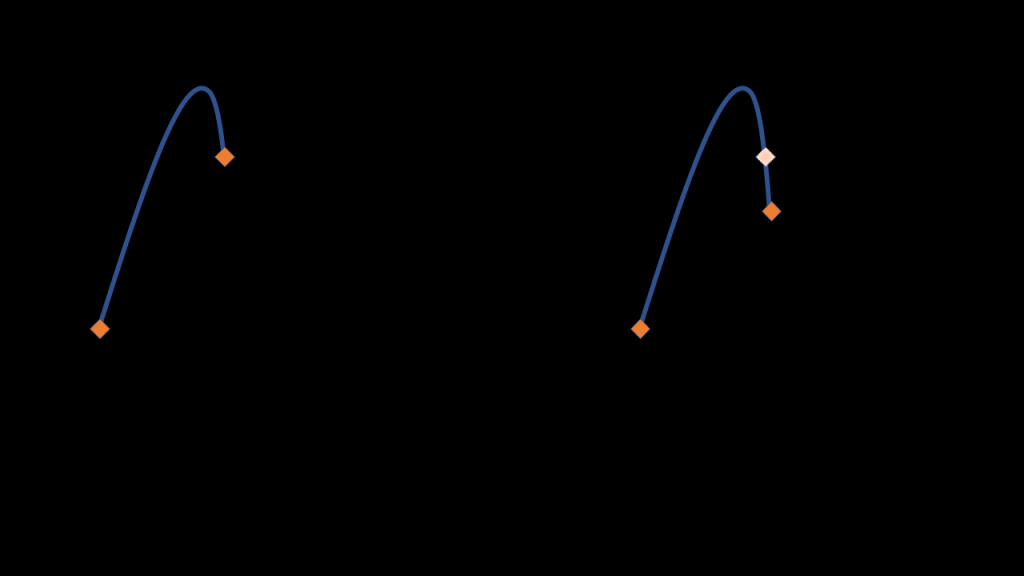

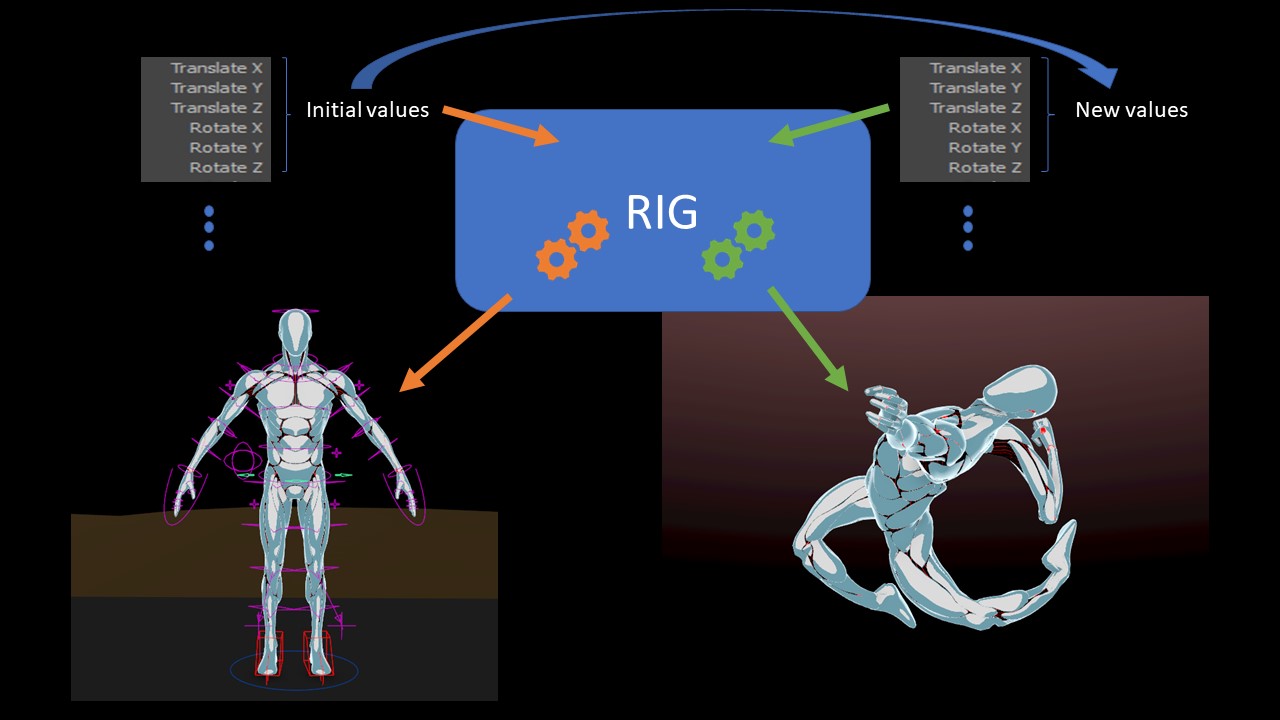

Step 1.2 Solver!!!!!

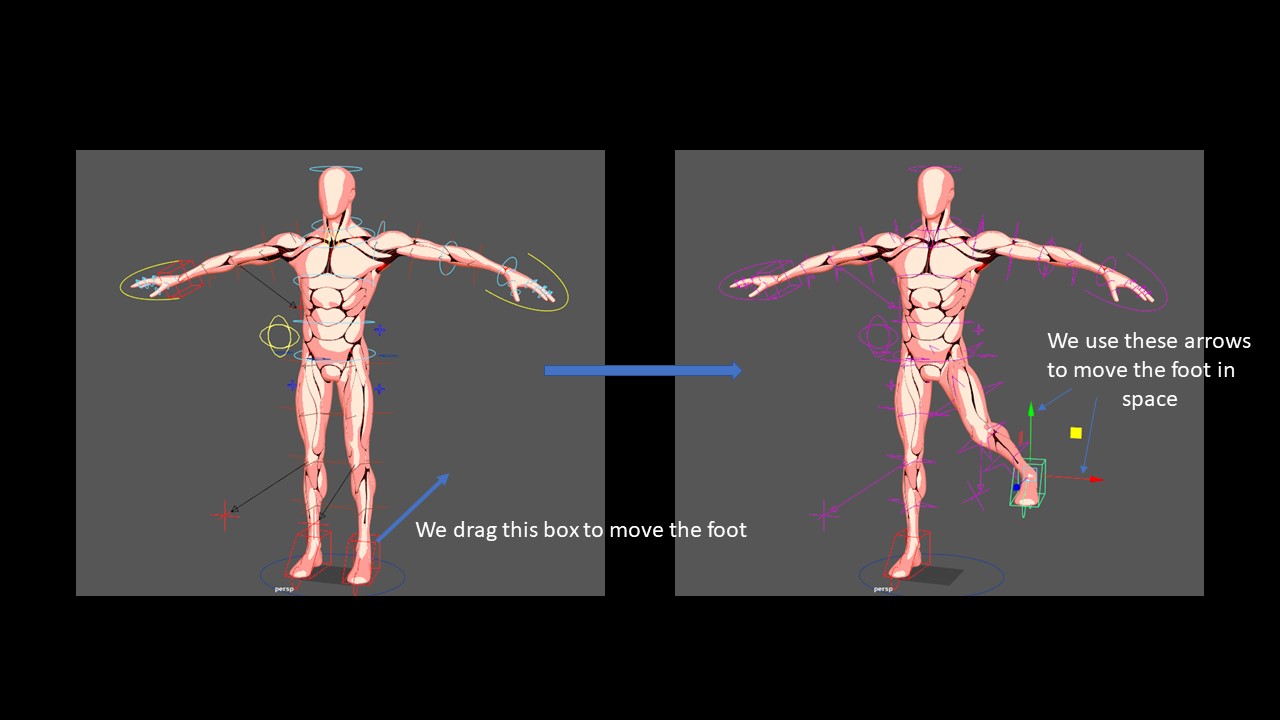

Now, let’s talk about our main interest: the Solver node. To use this guy properly, you first need to double click to enter into it and discovers its secret:

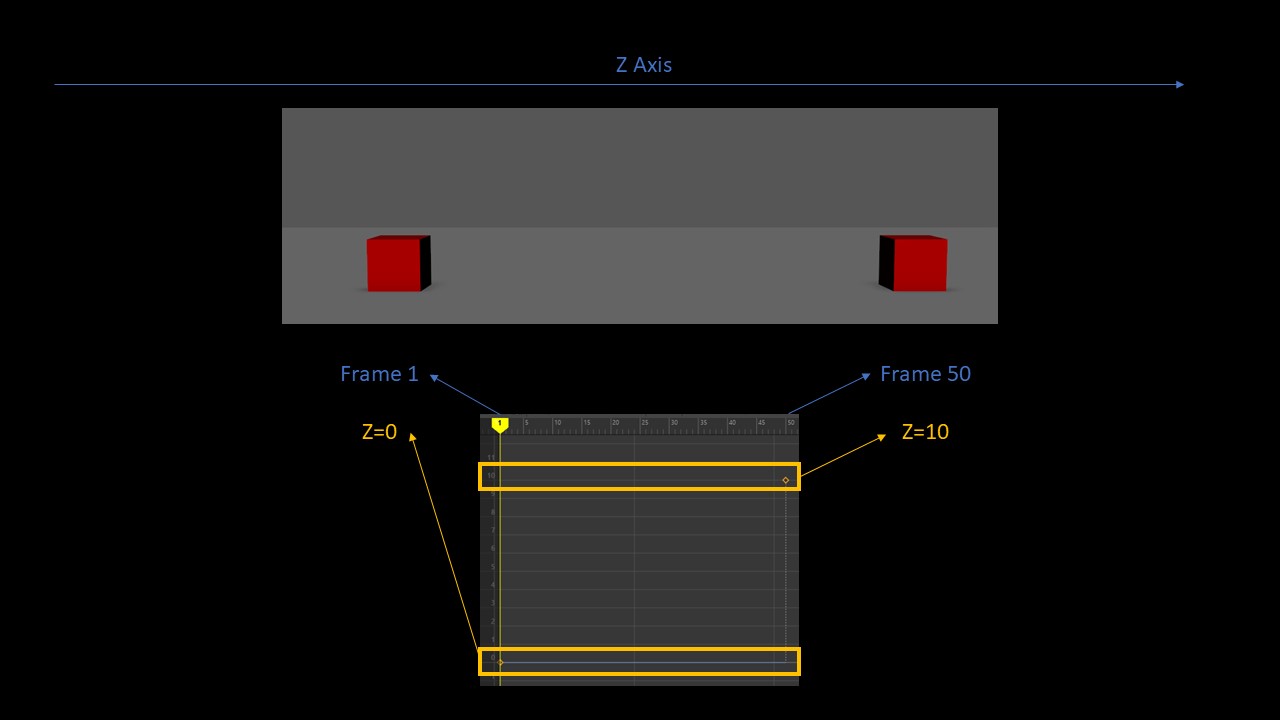

Basically, it’s the purple node that does the magic: using it, you can access your geometry parameters in the state they were one frame before. So for example if I write this:

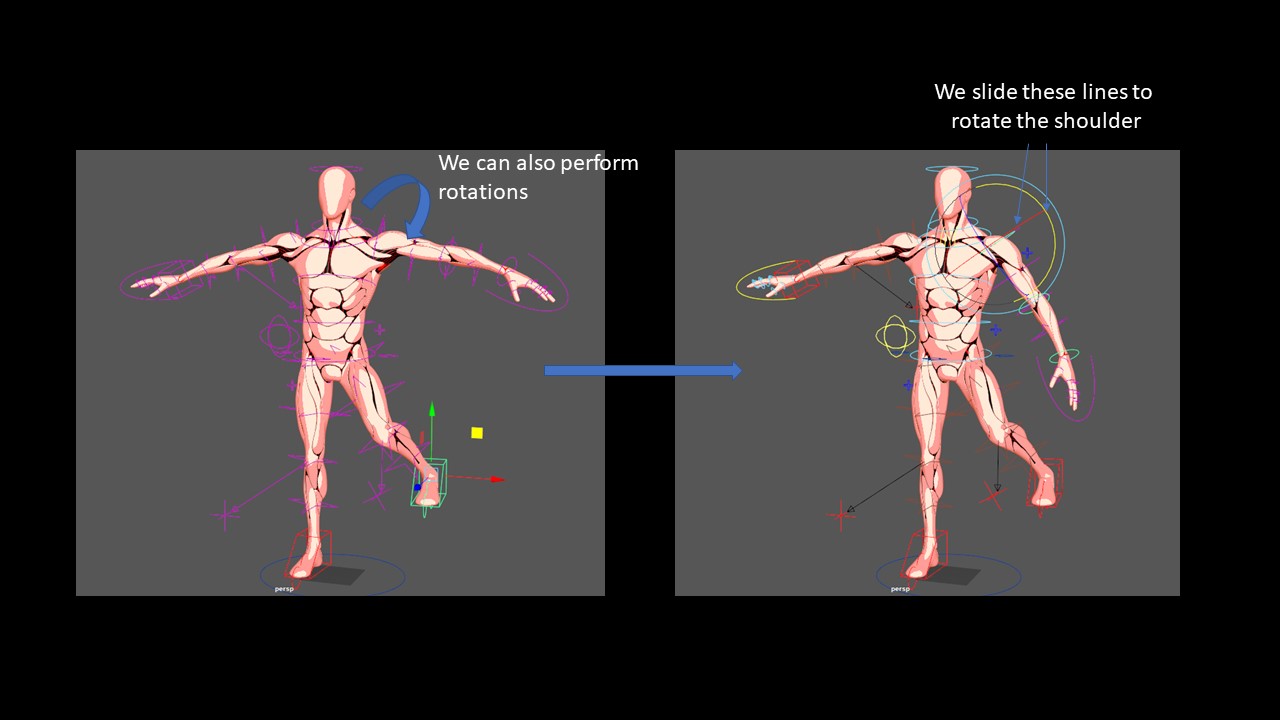

@P.y += 1;In a wrangle outside of the solver, it will just move my geometry of 1 unit along the y-axis and nothing more. But if I put this wrangle inside the Solver, the geometry will move of 1 more unit incrementaly at each frame!

It is a simple implementation of the rules I stated before. If you pay a close attention, I am not setting directly the attribute ‘cluster’ but an auxiliary attribute called ‘next_cluster’. I don’t really know how Houdini operates the parallel operations so I want first to get how I will change my points then change them ONLY when I figured out ALL the values I need to change (If by any chance you have infos on how Houdini parallelize the computations I would be really delighted to hear from you!). And that’s why I have a wrangle ‘update’ that will do exactly this:

Step 1.3 Setting colors

That’s just straightforward: set a color for each cluster and assign the right color to the right points:

Step 2. Making waves

This step was totally unnecessary but I find it pretty cool so I did it. Creating a wavy effect is pretty easy, most of the time you can achieve it by displacing along the normals with a cosine signal. But if you do not take anything else into account, everything will bounce at the same rythm and it will not create any waves.

To solve this problem, a standard way to do would be to choose a point as an origin for the waves and then multiply the displacement by the cosine of the distance between the current point and the origin. So, to make it short, having 2 sinusoidal signals, one in terms of time, the other in terms of position.

Here, rather than using directly the Euclidean distance (i.e the usual distance), I prefer using the birthdate (i.e the date of contamination) of our point. Actually, there’s a mathematical meaning to do that (I am not doing nonsense) that I explain in the next paragraph if you are interested.

Let’s talk math shall we?

What is interesting about this short example is that it lets me introduce some maths. Actually, there are 2 things I want to talk about: metrics and Voronoi diagrams.

Why does it make sense to use the birthdate in place of the distance for the temporal sinusoidal signal?

Short answer is: because we can define a pseudometric from it (basically, it means that it implements a notion of distance)

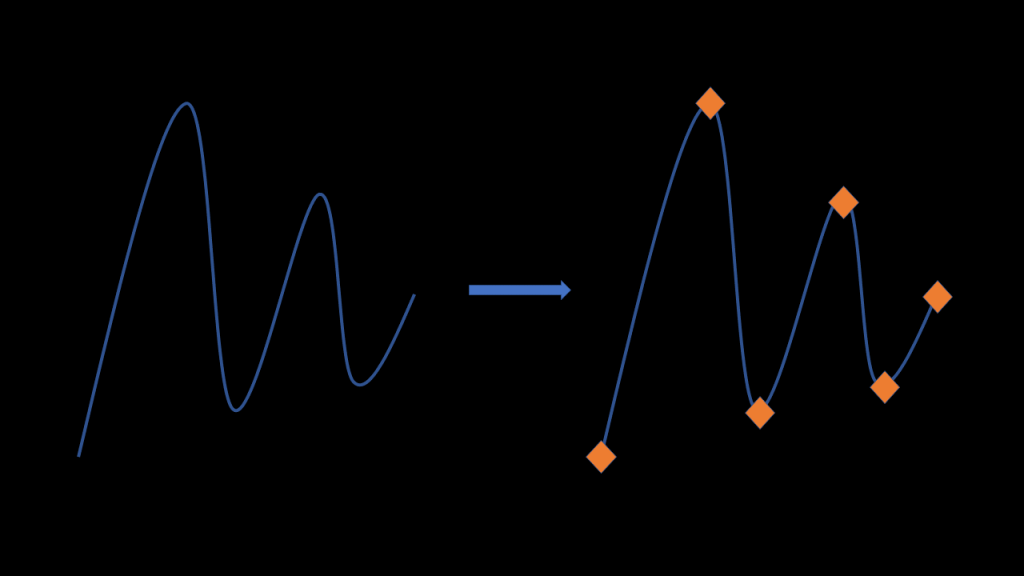

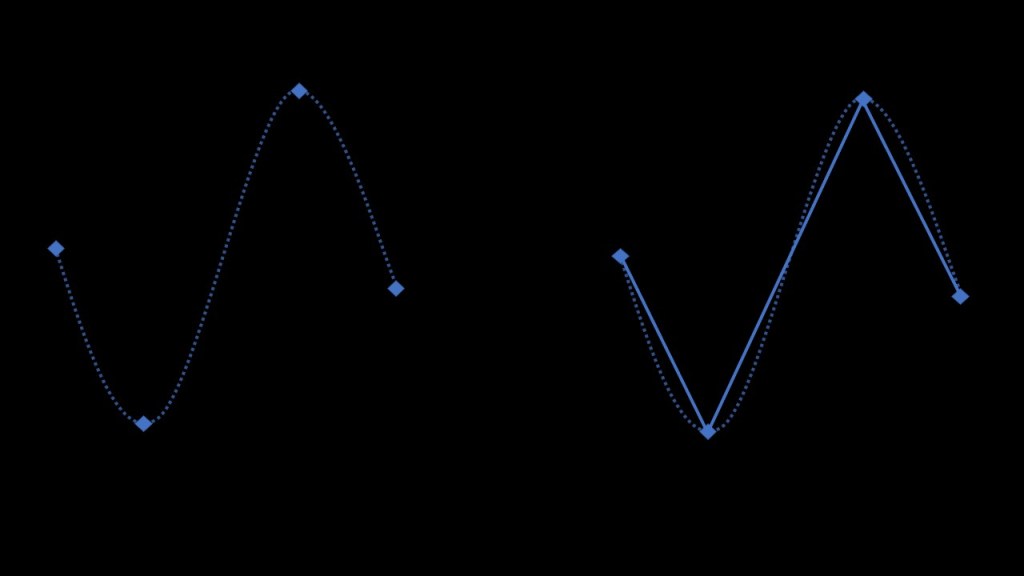

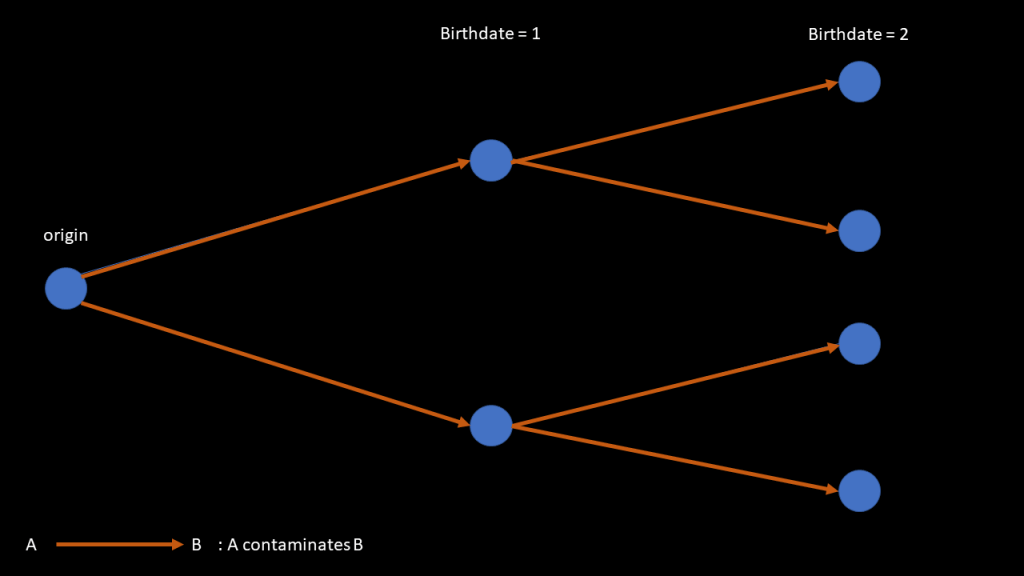

The way I am creating the contamination can be represented as a tree:

And I can define a pseudodistance for the elements of that tree by taking the difference of their birthdate: . What is a pseudodistance though?

So, a distance is used to evaluate how 2 points are far one from each other. A pseudodistance is merely the same, except that it fails at distinguishing 2 points: for a distance means that

while it is not the case for a pseudodistance. (check here for the mathematical properties. Proof that the difference in birthdate is a pseudo-distance is left to the reader lol)

So, even though my choice of using the birthdate was mainly driven by my laziness, it still made sense mathematically and was in some way even a better choice than using the Euclidean distance. Indeed, the Euclidean distance does not take into account at all the shape of my surface, while it is the case for my pseudo-distance (best case scenario would be to use a geodesic distance along the surface, but that’s hard to implement and to keep good performance using that).

About Voronoï fracture/diagrams

If you are used to play with Voronoï fractures in Houdini or with Voronoï diagrams in computational geometry, you probably have noticed that the clusters created by my thingy somehow look like Voronoï cells. And, guess what, it is not a coincidence.

Let me first recall you what a Voronoï diagram is (I’ll try to make a whole note about it later on because a short explanation might be confusing).

Notice that all cells only contain one black point that we call a seed. Basically, to obtain this diagram, first, I give you the seeds. Then, given a seed, its cell is the set of points that are closer to this seed than to any other seeds.

With our method, the closer a point is from the center of a cluster, the more likely it will belong to this cluster. So, a cluster will be approximately the set of points that are closer to the origin of this cluster than any other origins. And Iif you followed what I said earlier, it really looks like the definition of the Voronoi diagram. Which explains why it is so similar with the regular Voronoi diagram.

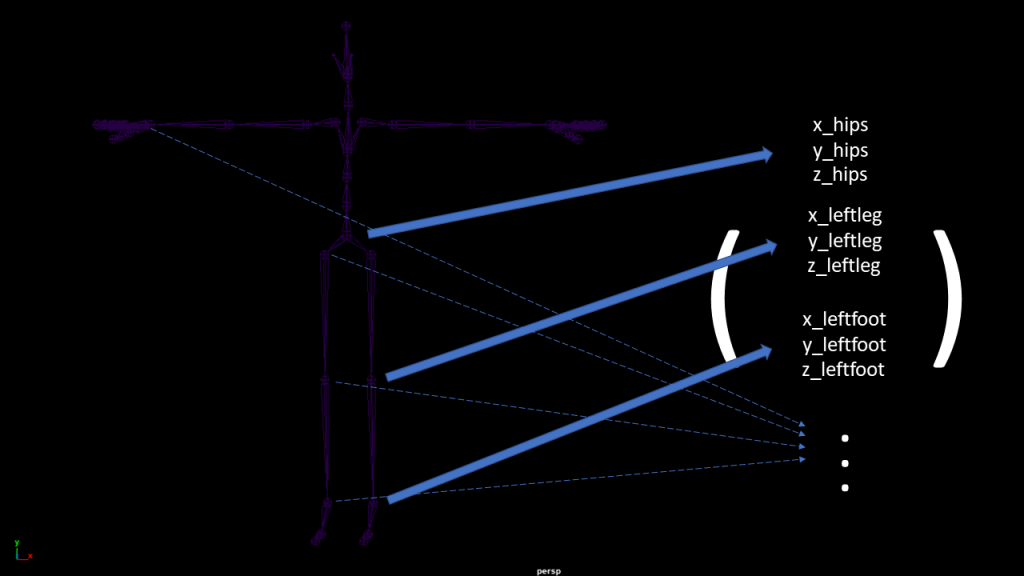

A more ‘advanced’ point of view regarding the Voronoi similarity

Thing is, the clustering we obtain is also a Voronoi diagram but with another distance. When I said ‘closer’ earlier, I immediately implied that there is an underlying notion of distance. In most cases, we stick to the Euclidean distance but we do not necessarily have to.

Indeed, I can define an asymmetric distance on my set of points by defining as the time it will take to contaminate x, starting from y, with the given procedure. We can prove it is defined, and verifies all the distance properties except the symmetry (ask me if you want the proof).

With this distance as the underlying metric, our algorithm exactly boils down to draw the Voronoi diagram! To be perfectly honest, I’m not sure how it is a relevant information though, as it sounds more like a tautology than anything but that’s cool anyway XD